In the Field With Fluffballs

A Day Spent with ʻUaʻu Kani Chicks

In the conservation world, when we are working on the land, we say we are “in the field”. I worked “in the field” fifteen years ago, but now most of my days are spent working “on the screen”. So, a couple weeks ago, I jumped at the chance to join HILT’s Land Stewardship Manager James Keoni Crowe at our Hāwea Point conservation easement to band ʻUaʻu Kani chicks. ʻUaʻu Kani (Wedge-tailed Shearwater or Puffinus Pacificus) are native seabirds that nest at low-elevation sites in burrows under sand, soil, and the roots of native coastal shrubs and trees. HILT holds a conservation easement over a thriving nesting site at Hāwea Point on Maui. Our conservation easement protects ʻUaʻu Kani habitat and provides public access along a coastal trail.

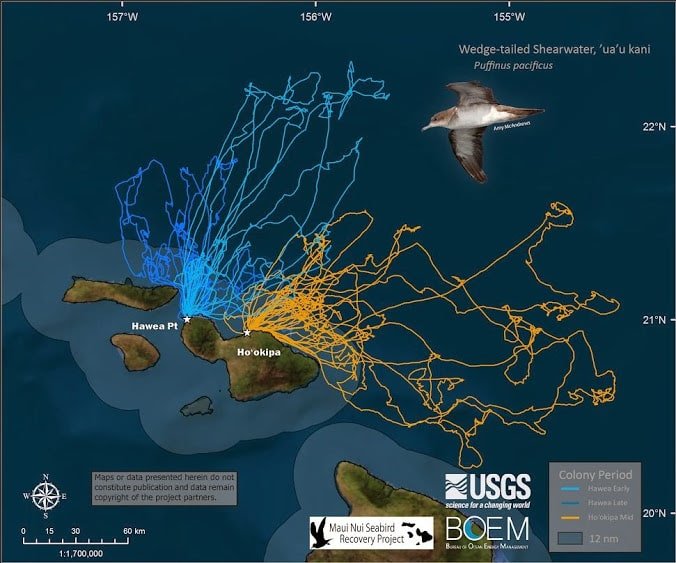

Knowing how much my friend and local designer Jana Lam loves birds, I invited her to join. Our Hawaiʻi Land Trust team of 3 was one of about 7 other teams from different conservation organizations and agencies at Hāwea Point for our annual banding day. Maui Nui Seabird Recovery Project organizes this annual banding day at Hāwea and works with USGS to track the ʻUaʻu Kani once banded so we can all understand the birds’ patterns and wellbeing. After circling up and getting our 30 metal bands and data entry device, we set out to our team’s designated area overlooking Namalu Bay. With James as the veteran bird-bander and Jana and I as newbies, we followed his lead.

“Step carefully. A burrow opening could be very small and it could extend way back,” instructed James. “Look for white guano or signs of digging.” Jana and I tiptoed about, sometimes laying flat on the ground to get a better look at a possible burrow opening. Soon James motioned for us to come over. When he gently pulled out the first ʻUaʻu Kani chick from its burrow - a grey fluffball with a long black curved beak - Jana squealed with delight. “Look at you! You are so cute. It’s okay, donʻt worry. We’ll band you quickly and put you right back,” Jana and I cooed at the birds, much to James’ dismay. I had just about as much fun watching the ʻUaʻu Kani as I did watching Jana admiring the ʻUaʻu Kani. We fell into a rhythm of Jana pulling out the ʻUaʻu Kani chicks and holding them, James skillfully banding, and me entering data on each chick. I also took a photo of each one, although they all looked similar...grey fluffball after grey fluffball. As we banded, locals and visitors on the coastal trail stopped to ask us questions. “We are banding these native seabird chicks, ʻUaʻu Kani, so that we can track their flight patterns, and how they are doing,” James explained. “They will wear these bands for their whole lives, about 40 years. Once these chicks leave their nests, they will spend the next 7 years on the ocean before returning to land. In 2005, there were just a couple mating pairs at Hāwea Point. Now, there are about 2,000 pairs here, and each pair produces one egg a year.”

I felt grateful being reminded of this conservation success, and HILT’s role in keeping the land undeveloped and accessible to the public. Iʻve heard stories of how Hawaiʻi used to have so many sea and migratory birds that at times, the whole sky would turn black with huge flocks arriving. We are a long way from returning to seabird abundance in Hawaiʻi due to coastal habitat destruction from development and invasive plants, predation by cats, dogs, rats and mongoose, light pollution which disorients birds, and the list goes on... But, at Hāwea Point, the population is thriving. I then looked out into the clear turquoise waters and could spot reef fish. Because the ʻUaʻu Kani have returned, it makes sense that the ocean waters are abundant. Seabirds are a critically important distributor of nutrients for marine ecosystems. Far out at sea, they feed on squid and fish, and then return to land, depositing through their guano (poop) with nitrogen-rich nutrients into the soil. When it rains, some guano nutrients enter the ocean and fertilize corals, sponges, and limu, increasing food and habitat for many other species.

After our day with the newest generation of ʻUaʻu Kani, I left exhausted, sore (my “on the screen” body is not used to being “in the field”), and full of hope and joy. I ola nā ʻUaʻu Kani!

— Laura Kaakua, President & CEO

HILT President & CEO, Laura Kaakua (left), and friend Jana Lam at Hāwea Point.

MNSRP and USGS Uau Kani Tracking Map - Hāwea in blue

Jana Lam, excited by every chick she found in a burrow.

HILT Land Stewardship Manager, James Crowe, expertly handles ʻUaʻu Kani for banding.

Nāmalu Bay offshore from Hāwea Point Conservation Easement